Jordan Hampton, Champion of Recovery

Stories of Hope

ARCHway believes in recovery from the disease of addiction.

Jordan Hampton shares his Journey of Recovery

As interviewed by Emily Jung

Jordan Hampton grew up in Farmington, a small town in Southeast Missouri. It was a football town, and Jordan was the star of his high school team. As captain, Jordan appeared to have it all. Everyone knew him and everyone liked him. He was by any other definition “a good ole American boy” as he put it. He had a smile on his face. He walked tall and confident. He was a leader.

But this was the Jordan everyone saw. On the field it may have seemed like he had it all together, but off the field he was struggling as he watched his own mother battling her addiction.

But this was the Jordan everyone saw. On the field it may have seemed like he had it all together, but off the field he was struggling as he watched his own mother battling her addiction.

He remembers being exposed for the first time to his mom’s struggles with substance use disorder at the age of ten when she got sober, and she would remain that way for several years. It was his senior year of high school that she relapsed. Relapse is a symptom of the disease of addiction. When a person has cancer, they go through stages. First, they may be treated with chemotherapy or radiation; this is hopefully followed by remission and later, a clean bill of health. But sometimes cancer returns, and it’s called re-occurrence.

The same is true with a substance use disorder. Their symptoms return, and they return to treatment where they look at what medications and techniques didn’t work before and what new medications and techniques they could try. Relapse does not mean the person failed. We wouldn’t tell a person who’s cancer returned that they failed treatment.

Relapse without a return to treatment can be fatal as is the case with any chronic disease, and for Jordan, who called his mom his best friend, you can imagine the toll it took on him. He realized his mom had relapsed the night of his senior prom. Prom was a big deal in such a small town, and every parent looks forward to taking pictures of their kids. Jordan’s mom was no different. She was the cool mom. She wouldn’t miss that moment for the world. At that point though, her addiction had control and she didn’t show up. Jordan shared that he was worried and scared for her. He didn’t know where she was or what had happened. His friends were asking about her, and he didn’t have answers. He wasn’t about to admit his suspicion that she was using again.

At this point Jordan hadn’t done much experimenting with drugs or alcohol. He had just started to dabble in marijuana, but prom night he was offered Adderall for the first time. And he was quick to take it in order to cope with the emotions he was feeling because of his mom’s absence. He explains that this was probably the first time he correlated emotional pain with drug use, and it wouldn’t be the last. Jordan quickly fell into codependency.

He went to Southeast Missouri State University, but this was a short lived attempt at a “normal” life. He began using more and more drugs, he started hanging out with a new group of friends, people who didn’t judge him for his drug use, and he was constantly going home to help his mom, chasing her out of bars and picking her up as she battled the disease. Jordan, himself, began to spiral quickly enough that, by the end of his first semester, he packed his stuff and dropped out of college.

Jordan continued to use drugs: Marijuana progressed to prescription pain pills which led to heroin and eventually methamphetamine.

He felt like his dreams were pulled out from under him. He didn’t have football anymore (which was his way of coping with the anger he had at the time), he had dropped out of college, and his relationships were crumbling. He was hurt by his mom, but there was also a lot of emotional pain because of what he looked at as his own personal failings. He hated himself for not doing what he set out to do and for turning to drugs himself. He felt unworthy, unloved and alone. His disease had control and his brain could no longer see that drugs could never fill the void he felt.

Around age 21, he began using with his mom; something that, during my first interview with him, Jordan couldn’t even bring up. He shared the first time he and his mom went to get pills together, both dope-sick and feening for more. They were in it together. They were codependent, relying on one another to keep using. They manipulated each other. They saw each other at their worst. Jordan would watch his mom overdose and bring her back himself more than once. He has guilt and feels he owes his mom because she was the reason they survived in that lifestyle.

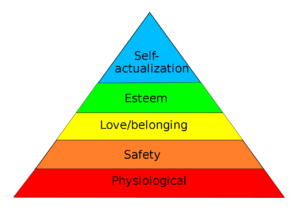

If we look at Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, we understand what our survival techniques look like. At the bottom are our physiological needs like air, water, food, shelter, sleep, and clothing. If these needs aren’t met, we compromise our need for safety including security of body, employment, and health, and we compromise our relationships, our self-esteem, and our morality. Addiction becomes about survival. Those suffering from opioid use disorder in particular aren’t shooting up to get high, rather they are using to prevent withdrawal symptoms and cravings. It’s an endless cycle as the effects of heroin only last between four and six hours.

If we look at Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, we understand what our survival techniques look like. At the bottom are our physiological needs like air, water, food, shelter, sleep, and clothing. If these needs aren’t met, we compromise our need for safety including security of body, employment, and health, and we compromise our relationships, our self-esteem, and our morality. Addiction becomes about survival. Those suffering from opioid use disorder in particular aren’t shooting up to get high, rather they are using to prevent withdrawal symptoms and cravings. It’s an endless cycle as the effects of heroin only last between four and six hours.

At this point in his life, Jordan and his mom were trying to survive, trying to meet their basic physiological needs and prevent withdrawal. And they would do anything, compromise anything, to get there.

As much as they kept each other using, they also kept each other alive. But this wasn’t the mother-son relationship that Jordan wanted or needed. He knew life wasn’t meant to be lived this way.

From there, Jordan went through a few years of stealing, going to jail and getting fired from jobs. Slowly but surely found himself with a completely different crowd of people. Jordan attempted an uncountable number of times to get clean, with little results. He tried different inpatient and outpatient programs, he tried ending his life, and he tried support groups to get clean.

Jordan shared his rock bottom with me. Broken and alone, he paints a picture of himself homeless in his hometown, having gone quite some time without sleep with rain falling all around him, the weight of this disease suffocating him. He remembers the next day walking to a park and breaking down completely. He describes himself crying, praying, and hollering out to the sky, asking God for help.

It was his step-dad, an ex-meth cook himself, who helped him set a boundary with his mom and started him on the path to recovery, proving the impact someone with lived-experience with the disease of addiction can have in this field. His dad got him a hotel room that night. It was there that Jordan decided he was going to start living life like he used to play football.

It was time to go to work, as Jordan puts it.

He found himself again at SEMO’s inpatient facility, and it was there he was introduced to Colton Baker, a peer support at the time.

Colton had one of the largest impacts on Jordan early in his recovery, something for which Jordan expressed his great gratitude. He instantly felt like he could relate. He thanks Colton for advocating and believing in him when he didn’t even believe in himself. He found a way to fund Jordan’s first month at Recovery House. He brought Jordan to the house on the day he was discharged from SEMO. There is no doubt that Colton was put in Jordan’s life for a reason.

Jordan quickly found his place at Recovery House. He remembers thinking, “I’m in the right place,” as he reminisces about playing football with the guys at Tower Grove Park within the first 30 days of his recovery. He explains how he was more than thrilled by the opportunity to manage the chores in the house, a job many would not appreciate, but Jordan looked at it as his opportunity to help. He wanted to be like the other peer supports and managers in the house that were seeing success after so much struggle, hardship, and pain. He looked up to those guys.

“I watched how they moved, how they grooved, how they made their lunch, set their alarm clock, anything, because I wanted more of what they had,” Jordan said. Their character, their positivity, their humbleness, was contagious to those who found themselves in the houses.

Jordan also gives a lot of credit to John Stuckey for believing in him when he got into transitional living. “It takes someone to come in and advocate for you [and] to help you believe in yourself…I discovered myself in that process. I discovered…that some of the things I dreamed of doing were not impossible – and I think John saw my desire to help.”

John would build him up and help put him on the right path. John believed in Jordan’s leadership abilities and his passion for helping others, as well as breaking the stigma around substance use disorder and mental illness.

Jordan carries his football team mentality into his work each day. He works as the director of Recovery House, as an EPICC outreach coach for Gateway Foundation, and is a peer support with NCADA and ARCHway. He wears many different hats because he is hoping to reach as many people as possible.

The Jordan people see today is the same Jordan on the inside as he appears to be on the outside. He is vulnerable and authentic to who he is, and he is able to share his story in order to help others struggling through this disease.

As director of Recovery House, Jordan is a role model for all those who walk through the door. “Be the example. Remember yourself when you first walked in that door… scared, fearful, insecure, broken. Take yourself back to that place and when you do that, you can reach out with tolerance, compassion, love for that person… we take a lot of pride in that.”

He models these character traits just as they were modeled for him by Colton and John. He promotes a culture of respect. As an EPICC outreach coach, Jordan drives all over the St. Louis area responding to high-risk opiate users who find themselves in the ER, ICU or a behavior unit.

“We have been entrusted to go in and speak with someone who might be at the most vulnerable stage of their life and let them know that there is a way,” Jordan explains. He walks side-by-side with his clients, advocating for them like others advocated for him, giving them chance after chance until they find themselves in recovery.

Jordan says, “It is an awesome opportunity to be a vessel of hope, to come in, bring some energy, get someone excited about the changes that are totally possible to make.”

Doing work with NCADA in their TCP Program (Transitional Counseling Program), Jordan works mainly with adolescents who have been caught at school with anything substance-use related. He works with kids educating them on the effects of drug and alcohol use, in hopes of preventing future use. He finds that, in these cases, it is most beneficial to develop the best possible relationship between adolescents and their family members. He believes it is important for parents and their children to have transparent, open and honest conversations.

Kids need a champion to go to for support.

Jordan has a support system. He works on his personal recovery. He sponsors others. And he continues to grow in his career. His relationship with his family is much improved, and although his mom is still struggling, he has the tools to cope in a healthier way without thinking first about going to drugs. His mom is in treatment but does fall back into active use every six months or so. It is hard for Jordan to see her and to watch her struggle.

Even while sharing his story with me, you could tell it forced him to take a walk down memory lane; something we don’t always want to do. However, Jordan knows his story can help so many others and that is why he shared this with us. He’s a testimony to the power of medically assisted treatment, community support, transitional living and, at the root, people who are willing to advocate for others, seeing potential and helping propel them further.

Jordan is part of a movement of peers.

He says we need to match the numbers. This epidemic isn’t going away. We need to continue to first help people recover and then show them that they, too, can help others. As Jordan says, “It takes champions.”

For more information about ARCHway Institute for Addictive Disease and Co-Existing Mental Health Disorders, contact:

ARCHway Institute for Addictive Diseases and Co-existing Mental Health Disorders

3941 Tamiami Trail Suite 3157-53, Punta Gorda, Florida 33950

Email: Emily.Jung@TheARCHwayInstitute.org

Phone: 314-635-8887

Website: https://TheArchwayInstitute.org/

Facebook: https://www.Facebook.com/TheArchwayinstitute/

Vimeo VOD: https://Vimeo.com/ondemand/archwaystoriesofhope